This link will take the reader to a video of an exceptionally deformed dog who

had a very short life. Since I was alerted to this Facebook post by a colleague, I have not been able to get this film out of my mind, having, as it does, appalling implications for the

welfare of dogs and highlighting how, inadvertently or deliberately, and by action or inaction, we may all be complicit in allowing such a state of affairs to continue.

I have reproduced the very eloquent post which accompanied the video, in full. It is written by a vet nurse who also works in rescue, and it encompasses all the ethical dilemmas faced and emotional trauma suffered by those attempting to care for these dogs.

“This feels like an impossible post to write, and it’s taken days to even be able to try and put it to words, but the Saturday before last, we lost our beautiful Winnie. Winnie came to us

back in May, she was due to be PTS after suddenly going off of her back legs, she was eight months old and deserved a chance, so we agreed to take her on. Winnie’s list of problems felt

never-ending, but she was incredibly happy and full of life, so we chipped away getting each issue sorted, both of us nursing her and giving her the extra care she needed throughout.

As the weeks and months went by, we watched her get better and better. Winnie loved life, she was a ray of sunshine, fun and playful and loving to everyone. She filled the space around her

with pure happiness and put a smile on everyone’s face, her issues meant she couldn’t do all that she wanted as a puppy but she never let it get her down. She truly was one in a million. After

all these months she was nearly ready to leave us, and despite all her problems we had found her a dream home, one you couldn’t have even imagined, she had won the lottery. So, she went to be

spayed and have her second BOAS surgery. The surgery went well and, although her initial recovery was uneventful, she was staying in the vets for close monitoring.

However, within 24hrs she suddenly went downhill and despite all the best efforts from an amazing team, she crashed and was unable to be resuscitated.

I can’t remember the last time a death has hit me like this, I don’t have the words to say how deeply, deeply devastated I am. To make it worse, my paid job as a vet nurse and the fact she

was at my practice and I was working that weekend, meant that I was there, involved from start to finish, even while her lifeless body was desperately trying to be revived, and although a part of

me is pleased I was with her at the end, the images are hard to get out of my head.

The veterinary world is rough at the best of times and despite what people might think, losing patients like this isn’t easy. You don’t just switch off and go home, you carry it on your

shoulders, and it adds an extra layer to my grief to know that my friends who tried so hard to save her also had this weight on them. I’ve spent the last week questioning everything, beating

myself up, doubting decisions that I made, replaying and scrutinising everything again and again and again, wondering if this or that may have made a difference. It’s made me question being

in rescue, made me question the job that I’ve done for over two decades, and made me feel unbearably low.

But the sadness and guilt is now turning into rage. We had no choice, she HAD to have the surgery, and this is always the risk. So now the question really is, WHY THE HELL are we still

breeding dogs that need to have operations for them simply to breathe? How earth does this make any sense? When did BOAS (Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome) surgery become so routine?

Can someone please explain to me how it is acceptable to breed dogs that then have to be operated on for them to survive??!

When I started vet nursing, BOAS was almost unheard of, and now at my practice we must do at least one surgery a week, it feels like it’s almost become acceptable. I’ve even heard clients

say, “Oh don’t worry, you can just get that fixed!” as if it was no different to a neuter. Winnie was not from a “backyard breeder” she was Kennel Club registered. She had cherry eye, entropion,

distichiasis, skin issues, hip dysplasia, chest infections, severe spinal deformities and disco-spondylitis. She was deaf, and before the first BOAS surgery, struggled to breathe with even the

slightest exercise. She was a mess, a total genetic freak.

But we are still pumping out more and more of these dogs to live, at best, disabled lives. It is absolutely criminal that this is happening. Winnie was a part of our family for the time she

was here, and her leaving has had a massive impact on us. I don’t often pour my heart out but I feel like it’s important for people to know what happened to her and for her short life not to be

for nothing. Winnie is not the first dog I’ve seen die from complications with BOAS and she won’t be the last. It is so unnecessary and unfair on the veterinary staff that have to care for

them, for the rescues who so often have to pick up the pieces and, most importantly, the dogs, whose lives are so restricted and affected. To everyone that helped to look after her for these past

few months, thank you from the bottom of our hearts. And to Winnie, I am so sorry. I’m sorry if I let you down and I’m sorry you were born like this, you deserved so much more, and you nearly

made it, but I hope you know you were so, so loved.

Enough is enough, we really need to stop breeding these dogs.”

My personal response

To begin with, I simply shared the post on my Facebook page, which garnered some relevant comments and pertinent emojis showing sadness or anger, but, upon reflection, I felt determined to try to air this heart-wrenching case further. Suffering as Winnie did from the full panoply of defects associated with brachycephaly, some may well say, with justification, that immediate euthanasia would have been the most pragmatic, practical and humane option. Yet the equally understandable human need to save a life and then care for it, particularly such an evidently joyful one, prevailed.

The knee-jerk response of blaming one’s pet hates and perceived culprits, (be it the Kennel Club, ignorant fashion-following owners or vets ‘just in it for the money’, to name but a few) is not helpful. I have identified several focal points at which, if appropriate action had been taken, vital information regarding the extent of this serious welfare problem could be gathered. These data could and should be used in the future to help, not this individual dog, but the future of all similarly affected breeds. To achieve this, the ‘stakeholders’ involved must be kept ‘on-side’ and involved in debate, rather than be forced to become defensive by levied criticism, even if such criticism is felt to be justified.

My immediate musings and questions were:

- How and why did Winnie come to need ‘rescuing’? Why did her owners first chose then discard her?

- Had anything had been done to inform the Kennel Club about this dog and her breeder? Were the puppies delivered by C-section? Was anything known about the fate of the rest of the litter?

- Had the bitch conceived by artificial insemination? If so, who carried out this procedure on a bitch very likely to go on to require a C-section to produce absurdly lucrative puppies? Who is routinely carrying out these Caesars? Who is routinely carrying out BOAS surgery?

- And then, possibly more controversially, are owners, unwittingly or deliberately, choosing dogs upon which they have to lavish thousands of pounds, first to buy the animal and then keep it alive? Is some grotesquely distorted version of social kudos gained thereby?

Winnie's history

Those involved in ‘’rescuing’ Winnie have been very forthcoming with all the information they have had about her. At the age of eight months and when still with her original owners, she suddenly

became weak and ataxic in the hind limbs. She was taken to her own vets who, the owners having no money for investigation and surgery, advised eight weeks of cage rest. The owners, who both

worked full time, felt even this was too much commitment and requested euthanasia. At this point, the vets contacted the rescue, who took Winnie in, and, following consultation with their own

vets where x-rays were taken, gave antibiotics for disco-spondylitis as well as the prescribed cage rest. Many other spinal deformities were evident and Winnie was referred to the Royal Vet

College for an MRI scan which confirmed her many issues.

Winnie did improve sufficiently to warrant initial BOAS surgery to remove 2cm of soft palate and correct the entropion and cherry eye. Two months later, she was thought well enough to be spayed and further BOAS surgery was carried out. However, despite everyone’s best efforts, she did not survive.

Focal points of current and future intervention

Although much of Winnie’s history was gleaned from her original owners as above, no questions were asked as to why the breed had been selected or whether any research into potential health problems had been carried out prior to purchase. The rescue was provided with Kennel Club registration documents for Winnie but the only connection with the breeder was provided by her original puppy vaccination certificate. There was no record of whether Winnie had been delivered by C-section. An attempt was later made to record Winnie’s disabilities and her first BOAS surgery with the Kennel Club as advised, but apparently the system was found to be too complicated and time-consuming for completion at the time.

No attempt was made to contact the breeder for further very pertinent information, such as whether Winnie’s mother had conceived via artificial insemination and if so, the name of the

establishment carrying it out. Further investigation as to how the sire was selected and the conformation of his breed line ought to be not only possible but essential.

Personal communication with Bill Lambert of the Kennel Club has confirmed that, although both breeders and vets are obliged to report all Caesarean sections and corrective surgery and some breeders do indeed comply with this obligation, very few, if any, veterinary surgeons do. Robin Hargreaves, ex-president of the British Veterinary Association, has even raised the possibility of disciplinary action against veterinary surgeons who perform elective and repeated caesareans on bitches whose puppies are expected to carry the same defects detrimental to welfare and that clients who request the same may be in breach of the amended Animal Welfare Act (Hargreaves, R. Vet Record letters Vol 191 No 9).

Incidentally, the rescue vet nurse also works for the PDSA, who routinely carry out many Caesars and much BOAS surgery on dogs belonging to cash-strapped owners. She has doubts at to whether any

of this is reported anywhere but has determined to find out.

Finally and fundamentally, how to change the hearts and minds of the thousands, if not millions, of owners-to-be who are not only drawn to such deformed animals, but also find the results of

their disabilities (a prime example being their perceived and convenient need for little exercise purely because they cannot breathe well enough) comical and cute. If the same selection for

‘cute’ disability were to be considered in human children, even the thought is quite sickening. How can it be tolerated in dogs?

In this respect, the customer is not always right. Veterinary surgeons should not feel obligated to cow-tow to their clients’ every wish, particularly when to do so perpetuates disability and

suffering. Of course, the individual pregnant and already whelping bitch must receive the surgery it needs but only on the understanding that she is neutered.

Media images of brachycephalic dogs must either not be used at all (the skate-boarding Bulldog used to advertise Churchill insurance being a prime example) or accompanied by mandatory health

warnings, in the same way as in early anti-smoking campaigns. Even genuinely rescued brachys and their owners risk acting as unwitting advertisements for deformity and the suffering it causes. We

must tell it as it is.

Additional initiatives by Kennel Club may be found here.

And this has all been said before in the (sadly late) Philippa Robinson’s presentation to the British Small Animal Veterinary Association congress in 2015 where her conclusions were that we

must:

1. Clarify what the health and welfare messages need to be for each breed/ type, based on evidence and good data

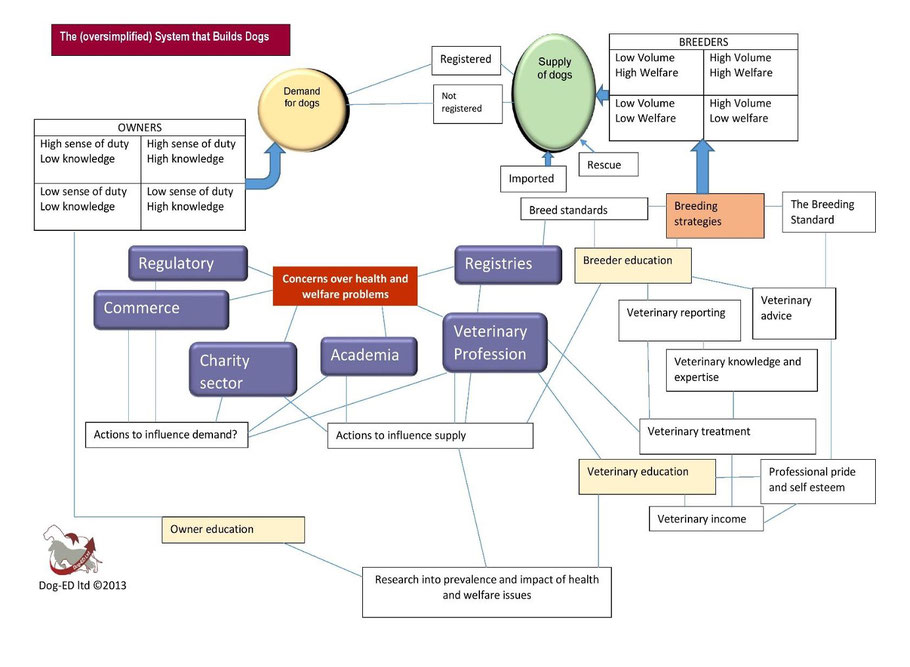

2. Really understand the dynamics of the system that supplies dogs and puppies – again mindful of breed/type

3. Really understand the human behaviour that determines our dog buying/ acquiring decisions

4. Simplify the key messages derived from numbers 1 and 2 to help us shape number 3

5. Deliver those key messages consistently across the board – messages to be delivered by ALL parts of the system

Finally, my own 2021 contribution to the debate – a viewpoint entitled ‘What to do about brachycephalic dogs?’ - can be found here.

What has become abundantly clear is that we are all, possibly inadvertently and through inaction, complicit in this intolerable state of affairs. Even those who do not like dogs or have a

cultural aversion to them, must realise the inherent cruelty in such extreme manipulation of conformation and appearance. Data collection is essential via all the channels already available, to

ascertain the sheer volume of suffering dogs. This must be able to be done as quickly and easily as possible if compliance is to be maximised. If this is not achieved voluntarily, then it must

become mandatory with potential legal and professional consequences, as proposed in Robin Hargreaves’ letter.

But fundamental human behaviour change is also of the essence as indeed highlighted by Philippa Robinson and also promoted by Suzanne Rogers and Jo White, co-founders of Human Behaviour Change for Animals, so that dogs such as Winnie are never created in the first place.

“By understanding why humans do the things they do and what drives them to change, we can make the world a better place for all animals”